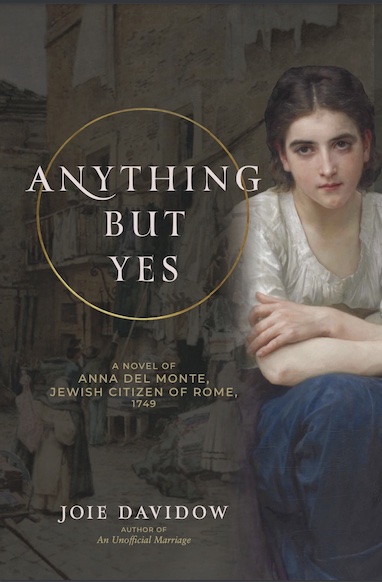

Joie Davidow

This beautiful new work of historical fiction was inspired by the diary of an 18th-century Roman Jewish girl who was imprisoned in a convent cell by the Catholic Church in an attempt to forcibly convert her.

“An intricately detailed novel of resistance and community.” —Kirkus Reviews

“In this beautifully written and meticulously researched novel, Joie Davidow lifts the curtain on Ghetto life in Papal Italy and the centuries-long effort of the Catholic Church to convert Jews to the ‘one true religion.’ The plight of Anna Del Monte illustrates the determination of the Church to baptize Jews, willingly or not, and the courage and resilience of the Jews, who were equally determined to maintain their culture and religion.” — Carolyn Valone, Professor Emerita, Trinity University

“A compelling account of the intersection of sincere faith and abusive political power.”—Mary Doria Russell, Author of The Sparrow and Thread of Grace

Anything but Yes is the true story of a young woman’s struggle to defend her identity in the face of relentless attempts to destroy it. In 1749, eighteen-year-old Anna del Monte was seized at gunpoint from her home in the Jewish ghetto of Rome and thrown into a convent cell at the Casa dei Catecumeni, the house of converts. With no access to the outside world, she withstood endless lectures, threats, promises, isolation and sleep deprivation. If she were she to utter the simple word “yes,” she risked forced baptism, which would mean never returning to her home, and total loss of contact with any Jew—mother, father, brother, sister—for the rest of her life.

Even in Rome, very few people know the story of the Ghetto or the abduction of Jews, the story of popes ever more intent on converting every non-Catholic living in the long shadow of the Vatican. Young girls and small children were the primary targets. They were vulnerable, easily confused, gullible. Anna del Monte was different. She was strong, brilliant, educated, and wrote a diary of her experiences. The document was lost for more than 200 hundred years, then rediscovered in 1989. Anything but Yes is also based on Davidow’s extensive research on life in the eighteenth-century Roman ghetto, its traditions, food, personalities, and dialect.

Includes Italian to English glossary

Excerpt

One bell. One hour after dawn. The light of a

Roman April rouses the narrow ghetto streets.

From balcony railings, worn garments in harlequin

shades of red, violet, blue, and green wave like

flags in the warm morning breeze. On the Strada della

Rua, a merchant arranges baskets overflowing with used

bits and pieces—tableware, kitchen utensils, doorknobs,

drawer pulls, hinges. Half-hidden in his doorway, a jeweler

sits at a table covered in worn black velvet, arranging

and rearranging his display of coral and silver.

Stray cats chase each other through the rubbish and

shadows of the alleys down to the Strada della Fiumara

on the banks of the Tiber where the air reeks of fish and

feces. Ancient stone houses slump shoulder to shoulder

like drunken old men, every decrepit room, every stifling

attic, every dank cellar, home to five or six people.

Women carry chairs out into the street, maneuvering

to find a shard of sunlight. Graying heads bend low,

nose to fabric, so that ruined eyes can see tiny stitches.

Calloused hands mend a linen tablecloth, reline a

jacket, add fresh lace to the ragged hem of a skirt. One

of the women is nearly bald, another’s neck is gnarled

by a goiter. Most of them are missing teeth. A woman

wheezes, shoulders rising with the effort of each breath,

then coughs violently, lungs clogged with lint and dirt.

Even the youngest of the women looks old. They are the

daughters of Zion, descendants of Rachele, Ester, and

Miriàmme.

On a rotting wooden landing near the Arco di Azzimelle, a woman stops beating dust from a rug and

leans over the railing to berate the ducks, goats, stray

dogs, and naughty boys who are causing a commotion

in the alley below. At the Piazza delle Tre Cannelle,

plump grandmother staggers from the fountain, a full

bucket balanced on her head. And in the tiny Piazzetta

del Pancotto, the aroma of freshly baked bread breezes

about, momentarily cloaking the stench of the public

toilets.

Near the Piazza delle Cinque Scòle, elegant English

gentlemen in search of souvenirs use silver-tipped walking

sticks to poke through crates of cheap treasures—a

mosaic rendering of the Coliseum, a fragment of marble

statuary scraped and pounded to appear ancient. Ladies

examine etchings of squalid streets made quaint, holding

the cards away from their faces with gloved fingers.

Just outside the Gate of Severus, four guards, young

and muscular, joke and laugh, kick the cobblestones with

the tips of their boots, adjust the pistols lodged in their

belts. While on the other side of the gates, street peddlers

wearing the yellow caps that mark them as Jews throng

the Piazza Giudea, their wares tied up in bundles or piled

onto pushcarts. They wait impatiently, indignantly, not

daring to raise their voices. This is an old game the guards

are playing, dawdling past the hour when the heavy iron

bars should be lifted, the gates opened.

I I Wouldn't Leave

Rome to Go

to Heaven

Marked for Life

Infusions of Healing

Las Mamis

Las Christmas